When I was about 5 or 6 years old my aunt came to visit us. It was summer and my sister and I were playing in a small kid’s swimming pool in our backyard. Suddenly I saw this drawing on my aunts shoulder of a bear and asked what it was. “That is a tattoo” she answered. I thought it was pretty fascinating and from that moment I knew I wanted something like that on my body when I was old enough.

Despite the fact that most of the people in my environment had hoped I would have given up this tattoo idea, I designed my first tattoo when I was 18. Not soon thereafter I had it inked. After that I got two more. My tattoos are personal and I view them as an extension of who I am as a person, a part of how I create my identity. Although my tattoos are small, people have reacted in a judgemental way saying that it is a waste of my body and that only criminals get tattoos. Obviously I also had people asking me if it hurt, if they are real and what they would look like when I am an old lady of 60+. What was so annoying and interesting at the same time is that people would say your body, which implies I have some kind of agency over it. Yet they seem to want to (social) control my body.

In cultural anthropology the body can be studied to explore and understand a culture of a society.

French sociologist Marcel Mauss argued in his article “Les techniques du corps” (1935) that the bodily techniques we use (eating, sleeping, walking, sitting, having sex, etc.) are culturally learned. He stressed that every kind of bodily action carries the imprint of (cultured) learning and with this argument asserted that there is no such thing as natural behaviour.

British anthropologist Mary Douglas viewed the physical body as a microcosm of the social body (society) (Douglas 1970: 80). She argued that societies respond to disorder by classifying both natural and social things. Douglas wrote that the social body constrains the way in which the physical body is perceived through categories and its accompanying rules (such as pure and impure). The body, she stressed, is the most natural symbol for and medium of classification and therefore acts as a representation of the social body.

“The physical experience of the body, always modified by the social categories through which it is known, sustains a particular view of society.” (Douglas 1970: 72)

With that she meant that the two bodily experiences (physical and social forms of the body) continuously interact, reinforcing each other’s categories. Douglas argued that because of this interaction the body itself is a highly restricted medium of expression, because it is a form of social control and at the same time it is being socially controlled.

In Western society tattoos were long associated with marginalised groups such as sailors, criminals, soldiers and people who made their living as a circus act. The tattooed bodies, in this regard, can be viewed as ‘impure’ or ‘disorderly’ and something that may threaten societal values. However, people do not solely get tattoos or other kinds of body art because they want to be different or resist existing social order. By using photographs I took at the Amsterdam Tropenmuseum exhibition “Body Art” (which I visited on my birthday) I want to show you the many different ways tattoos and other forms of body art are used throughout different cultures around the world. A special thanks to Chrissie, intern Marketing at the Tropenmuseum, for sending me the little textbook of the exhibition!

Rite de Passage

Dutch-German-French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep coined the term “rite de passage”. With this he means the rituals that take place before or after ‘life changing’ situations such as, birth, weddings, funerals and puberty. These rituals depict or facilitate the change, or transition, in the social or sexual status of an individual. Van Gennep argued that these rite de passages have three stages: separation, liminality, and incorporation. In the first phase the individual separates him/herself from their current status and prepares to move to another. The second is the transition phase, liminality, and is the moment between states. In this phase the individual has moved away from his/her former status, but has not yet entered the next. In the third and last phase, incorporation or reaggregation, the individual re-enters society with his or her new acquired status.

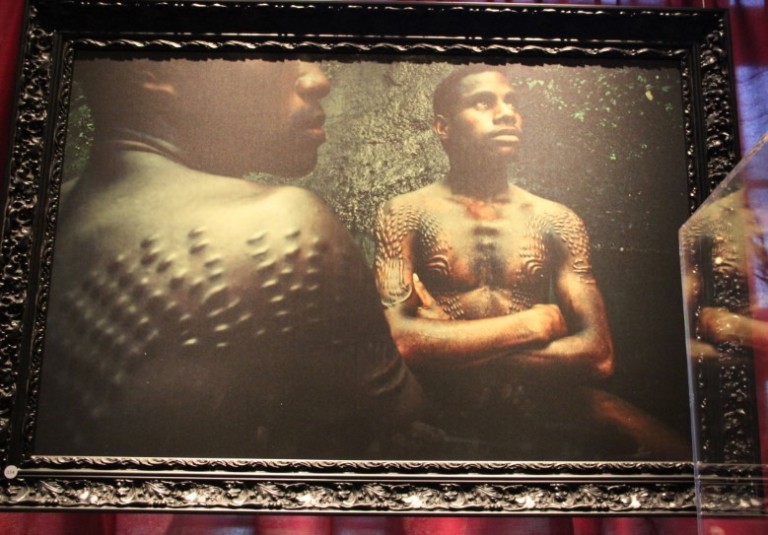

In Papua New Guinea along the Middle Sepik River lives an ethnic group that the anthropologist Gregory Bateson named the Iatmul (Bateson 1932). However, the people themselves do not identify as ‘Iatmul’, but in relation to their lineage, clan or village. Nonetheless, the ethnic group uses scarification as a rite de passage for young men. In this ritual the upper back and chest of the men are scared in a pattern that represents the most important animal in their mythology, the crocodile. The blood that is lost during the ritual is symbolic for the mother of the man undergoing the scarification. Without their mothers blood, they now have become men.

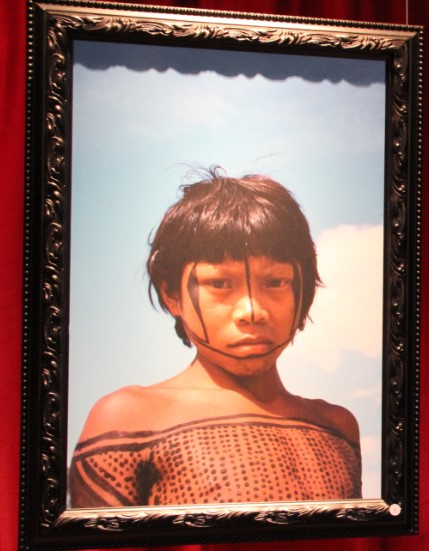

In the Amazone basin among the Araguaia River live the Carajá or Karajá people. In this indigenous group body painting has a highly symbolic relevance. The designs often represent natural species, especially fauna and are made with genipap fruit, as well as charcoal and annatto dye. The boy in the picture has gotten body paint because he is going to school for the first time.

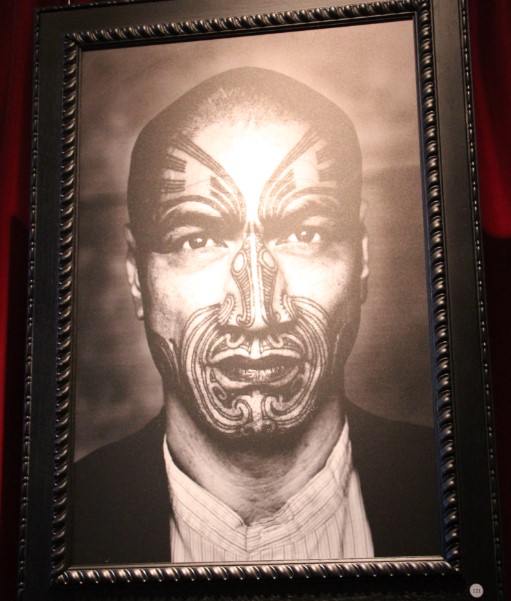

Vic Taurewa Biddle.

The Māori are the indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand and have a long tradition of Tā moko (face tattoo), which is distinct from tattooing. With tattooing the ink is being placed underneath the skin by a pinching needle, whereas Tā moko is traditionally done by carving which leaves the skin with grooves. This practice was done with uhi (chisels) that were made from albatross bone.

Receiving moko established a rite de passage from childhood to adulthood. Nowadays Tā moko is also done with tattoo machines and is a means of expressing Maori identity. The photo above shows Vic Taurewa Biddle moko. In this clip below you can hear him explain what his moko means and also how homosexuality is seen within Maori culture.

As you will later read in this blog, tattooing is also done to show the wearers status and rank. In the old days only high-ranking persons could receive moko, those who did not have a moko were seen as to have a lower social status.

“Short Interview with Vic Taurewa Biddle” Uploaded by nervid, 2008.

Spiritual

Left: Photo by Unknown photographer, Kalimantan, Indonesia, early 20th century.

The man in the picture is of the ethnic group Ot Danum Dayak (which translated means: people who live upstream the river), who live in south of the Kapuas River bordering West- and Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Tattoos in Ot Danum Dayak culture represent their cosmos. The tattoo the man in the picture has represents the holy tree and rhinobird to give him protection against evil spirits and strength.

Middle: Tattoostamps made of wood from Kenyah, Kayan and Modang Dayak culture.

The indigenous people of Kalimantan, Indonesia are called Dayak and can be divided in different ethnic subgroups. Ot Danum Dayak, Kenyah Dayak, Kayan Dayak and Modang Dayak are among the 200 ethnic supgroups in Kalimantan who all have their own culture, language and politics. Traditional Dayak tattooing (Kalingai or pantang) is done to signify life experiences and journeys. They are thus also used as a rite of passage, like the tattoo of a eggplant flower (Bunga Terung) which was tattooed on a young men as he goes from boyhood into manhood. Tattoo stamps were used instead of needles, the designs were carved out of wood and were then placed in ink and stamped on the skin, where later the design is gone over again with a needle.

Right: Photo by: Reza/ Webistan/ Carbis, 1992. “Girl with Coptic cross”.

The placement of the Coptic cross on the inside of the right wrist is a sign of Christianity and devotion.

In India there is a festival honouring and celebrating the deity Angalamman in which participants paint their faces in the colours of the goddess.

“Yantra, the sacred ink” by Cedric Arnold. Bangkok, Thailand. 2014

Yantra tattooing, or Sak Yant, is practised in Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. It is believed that the sacred geometrical, animal and deity designs in combination with Pali phrases are magical and bestow strength, protection, and fulfil wishes to its bearer. The tattoos are placed by a Bhuddist monk or wicha (magic) practitioners with a khem sak (long metal rod with a point). Because it is believed that the tattoos decrease in power over time, the Sak Yant come together once a year and go into a trance together as is shown in the video above. You can find more photos of Yantra tattooing made by Cedric Arnold here.

Concealing beauty

This woman is part of the Apatani ethnic group who lives in the Ziro valley in the Lower Subansiri District of Arunachal Pradesh in India. This practice of tattooing women’s faces and placing yaping hurlo (nose plugging) is not done since the 1970’s. Because the Apatani women were known as the most beautiful women in the region, it is believed that they were tattooed and got yapping hurlo to conceal their beauty so that raiders of their village would not take them away.

Status & Wealth

This portret is of Purei, a 96 years old woman of the Kenyah-Dayak. Kayan Dayak adolescent girls were also tattooed as they would enter womanhood. However, only aristocratically women were allowed to have specific designs tattooed, as they were believed to be strong enough to resist any magic connected with the designs. The earrings Purei wears are also a symbol of wealth. The stretching of the earlobes is a direct result of the adding of bigger and more earrings, which also increases someone’s social status. The earrings Purei is wearing are made of brass, while in other cultures (like in Sumba, Indonesia) they also can be made of gold. See the original, much clearer photo here.

If you want to contact me, please leave a comment or you can follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

Excellent Web page, Preserve the good job. Thanks! http://bit.ly/2f0xJ92

LikeLike